The self-trivialisation of software development

Software development has an intricate relationship with complexity. As developers, we pride ourselves in solving hard problems. But there is a paradoxical instinct behind this: The desire to solve complexity so thoroughly, that it won’t have to be solved again. We aim to make complexities feel trivial. The best solution is often one that abstracts away the ugly details and turns a task that was once painstaking into a simple library import or one-line function call. This phenomenon, which I call the “self-trivialisation” in software development, means that by solving problems and sharing the solutions, developers effectively reduce the need for their efforts for further development that area. Well, at least until new complexities emerge.

C.A.R. HoareThere are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies, and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.

Self-trivialisation aligns with the first approach: tackling complexity by eliminating it through simplicity and abstraction. In this article, we will explore the history of this mindset, how it manifests today, what motivates it, and what it might mean for software developers in the long term.

A brief history of solving complexity once (and for all)

From the very beginning of computing, developers have looked for ways to abstract complexity and avoid re-solving the same problems. In ye olde days (and I am not writing this as a witness), programmers moved from writing raw machine code to using assembly languages, and then to more “high-level” languages like COBOL. Step by step, they made programming tasks more approachable by trivialising lower level details like managing memory or CPU instructions. This set the stage for the core idea of self-trivialisation: solve it once, reuse it everywhere.

By the 1970s and 80s, the practice of code reuse was emerging through subroutine libraries and modules. These were often distributed with compilers or sold by companies. This way, developers incorporated someone else’s well-solved solution rather than writing their own. As one history notes, even in these early days “code was already being reused in the form of libraries” to handle common operations on hardware or databases. However, this was largely a closed, vendor-driven model; updates were infrequent and sharing was limited.

The big turning point came with the rise of the Free Software and open-source movements in the 1980s and 90s.

Richard Stallman, The GNU ManifestoThe fundamental act of friendship among programmers is the sharing of programs.

Stallman’s philosophy, combined with the spread of the Internet, led to a collaboration boom. Developers around the world began sharing their solutions openly, allowing others to build upon them. By the late 90s and early 2000s, during the dotcom bubble, code reuse became a living process: libraries and frameworks were now maintained by communities and constantly evolved to meet new needs. If someone discovered a bug or improvement in a shared module, everyone who used it could benefit from the fix almost immediately. Essentially, whole problem domains were being solved once and then abstracted away for good.

- Operating Systems make CPU scheduling and disk management someone else’s problem.

- Programming languages and compilers allow us to use high level languages that trivialise manual machine coding.

- Garbage collectors eliminate a whole class of bugs like manual memory leaks.

- The web and all of its frameworks turned complex request handling into convention driven exercise.

What used to take a team weeks to build, we can now scaffold in minutes by simply importing NextJS, Laravel or .NET.

Libraries for everything

By the 2010s, package managers (npm, Maven, etc.) and open source libraries had grown so abundant that almost any common problem likely had an existing solution online. Modern software development often starts with searching for libraries or APIs before attempting a new implementation. As a result, developers spend more time integrating and configurating, rather than creating from scratch.

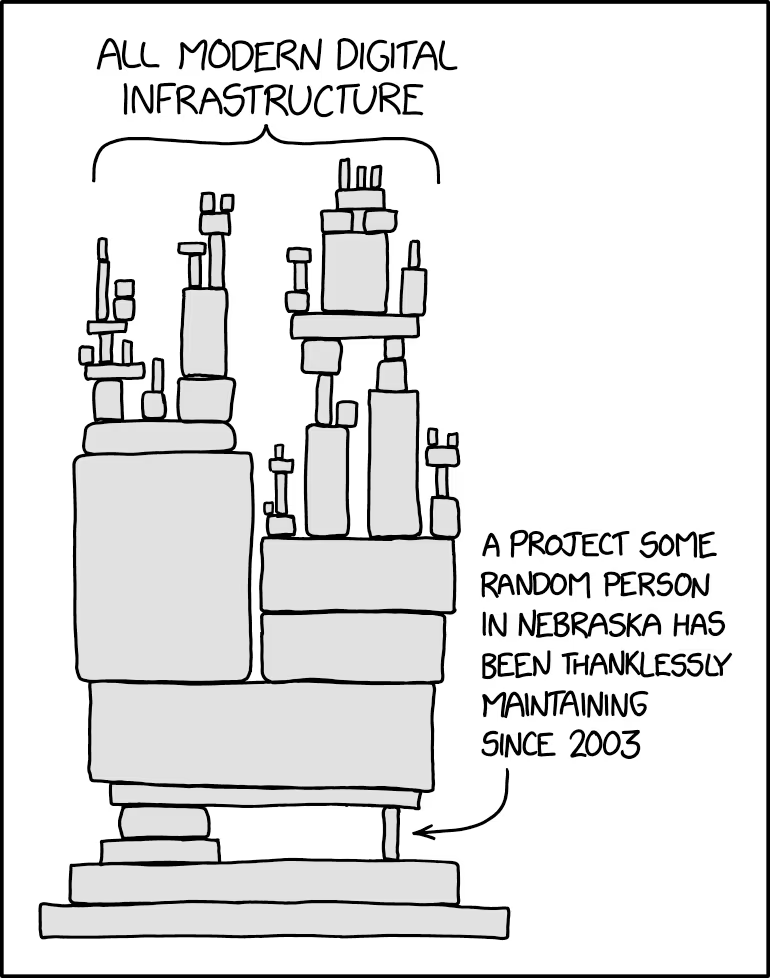

Small tangent: An awkward illustration of how far “libraries for everything” has gone, was the 2016 incident involving an npm package called left-pad . This was an 11-line JavaScript function for padding text. While the left-pad source includes tests and its logic has some validations going, it still seems like something any decent programmer could have written in a few minutes. Yet, because it was published as a package and many other packages depended on it, thousands of projects broke because the author removed the package from the registry. In other words, even a trivial problem (padding a string) had been solved once and turned into a shared trivial solution, to the point that many developers never bothered solving it again themselves.

This incident was an eye-opener: it showed that modern software is built on layer upon layer of prior solutions. In fact, almost all software is built on top of other software, which also depends on other software. The collapse of even a tiny layer can have enormous ripple effects.

Through these historical trends, we see self-trivialisation as a driving force in our field’s progress. Each generation of tools pushes out the frontier of what is “easy”.

Tasks that were once considered complex enough to define a developer’s job can become baseline utilities in the next era. This frees developers to focus on new, unsolved problems but it also means we are constantly standing on the shoulders of giants (or left-pad).

How Self-Trivialisation Manifests Today

In contemporary software development, the instinct to “abstract away the hard stuff” is alive and well. For example, I recently wrote an article about how we adopted React as a core pillar of our cross-department shared tech stack at OWOW. We see it manifest in multiple areas, from everyday coding habits to the general dev culture.

Dependency-first development

Today’s developers often approach a task by first asking, “Is there a library or service that already does this?” Rather than reinventing the wheel, we incorporate existing packages. The npm ecosystem for JavaScript, for example, contains hundreds of thousands of packages, from the complex (like React) to the incredibly simple (like left-pad). This means that implementing a feature may be more about choosing and integrating the right pre-made components than about algorithmic ingenuity on the developer’s part. After all, if the solution is out there and free to use, why not take it?

Open Source & “solving it in public”

Open-source software is arguably the purest form of self-trivialisation at scale. When a developer or team solves a hard problem and releases it as a free library or tool, they effectively trivialise that problem for the entire community. Need a robust web server? Use Apache or Nginx; nobody writes one from scratch today unless for learning or very special needs. Need an encryption algorithm? Use OpenSSL. Thanks to open source, the visible need for custom development in many areas has disappeared; we all share the same battle-tested building blocks. The culture of open source also encourages a kind of virtuous cycle: “I solved this hard problem, now you don’t have to, and you can even help improve my solution for everyone’s benefit.”. The result is that many developers spend more time on glue code and configuration rather than inventing fundamentally new pieces of software.

DevOps and Automation

Nowhere is “automating the pain away” more embraced than in DevOps. DevOps engineers constantly write scripts and set up pipelines to make manual, complex processes trivial at the push of a button (or the push of a commit?). Configuration management tools (like Ansible, Puppet, or Terraform) and CI/CD pipelines (Jenkins, GitLab CI, etc.) turn what used to be multi-step, error-prone deployment chores into one-click or fully automated routines. You could say the goal is to automate yourself out of a job. In practice, automating yourself out of the current job just means you will focus on new, higher-value tasks. Cope: The job evolves rather than disappears (we’ll revisit that point later). What once required dedicated operators and lots of careful hands-on work can now often be handled by a handful of lines of code or entirely handed off to cloud automation. DevOps is essentially the self-trivialisation of IT operations.

No-Code & Low-Code Platforms

The movement toward low-code or no-code platforms is another facet of trivialisation. Services like Zapier, SquareSpace, Framer, or AI builder tools aim to let even non-programmers create applications through visual interfaces and pre-built modules. They extract the expertise of common software workflows into configurable components that anyone can snap together. This trend takes the idea of “solving it once for everyone” to its extreme: the target user is someone who doesn’t know how to code at all, but can leverage what developers have pre-solved.

A small business owner can set up an e-commerce site via Shopify or WordPress with plugins, accomplishing in a day what would have taken a whole dev team months to custom-build 20 years ago. While professional developers might not use no-code builders for complex products, they themselves benefit from higher-level frameworks and cloud services that remove entire layers of concern. Today, a developer building a web app can rely on cloud infrastructure (no need to manage physical servers), use serverless functions (no need to manage server runtime), authenticate users via an API (no need to write auth from scratch), and so on. Each service or framework is trivialising a slice of the stack.

Generative AI

The latest form of trivialising development is AI. AI-powered coding assistants like GitHub Copilot, Claude Code, Cursor or large language models (ChatGPT and similar) can generate code snippets, functions, or even entire modules based on natural language prompts or existing code context. This means that many boilerplate or routine coding tasks can be handled by an AI suggestion in seconds, rather than written manually.

Read my TypeScript vibe coding meta.

While AI is not infallible and still requires oversight, it represents another layer of abstraction: it abstracts the act of writing code itself. We are reaching toward a point where a developer might focus more on describing the problem and desired outcome, and the AI handles the implementation details. This is self-trivialisation on-the-fly: each individual developer can now benefit from the collected “solved problems” of the entire programming community via an AI assistant. It’s a strong hook for the future of development, and one that raises new questions about what skills developers will need going forward.

Import, run and move on

In all these ways, the pattern is consistent: identify something hard or tedious, solve it (or automate it) once in a general way, and then reuse that solution forever. What was once a challenge, becomes a basic utility.

Jeff AtwoodIt’s painful for most software developers to acknowledge this, because they love code so much, but the best code is no code at all. Every new line of code you willingly bring into the world is code that has to be debugged, code that has to be read and understood, code that has to be supported. Every time you write new code, you should do so reluctantly, under duress, because you completely exhausted all your other options. Code is only our enemy because there are so many of us programmers writing so damn much of it. If you can’t get away with no code, the next best thing is to start with brevity

Atwood’s sentiment captures the developer’s drive to not solve something again if it’s already solved. Use the import, call the API, run the script and move on to the next problem.

Motivations

What drives this instinct to self-trivialise our work?

Among Larry Wall’s (creator of Perl) “three great virtues” of programmers, is laziness. Not laziness in the sense of doing nothing, but in the sense of expending effort now to save far more effort later. A good developer would rather write a program to do a repetitive task (and share it) than have to do that task by hand over and over. This productive laziness is a huge motivator for automation and abstraction. If something is tedious, we feel compelled to fix that by coding a solution. By doing so, we not only save ourselves future work, but also often share the solution so others won’t endure the same thing.

Next is impatience; the flip side of laziness. Impatience is the annoyance we feel when a process is too slow, leading us to make things faster or more efficient. Developers are often impatient to see results. If setting up an environment takes too long, we script it. If deploying code is slow or requires waiting on another team, we streamline it. The overall effect is a push towards faster iteration by removing as much friction as possible, which naturally means using existing solutions or automations whenever available. Impatience, in a productive sense, motivates the creation of tools that make development flows trivial and instantaneous (hot reloading code, automated cloud deployments etc.).

The third virtue is hubris: Pride in our work that makes us want to create something that others will not criticise. This relates to trivalising problems in a few ways: Developers often take pride in creating a general, solution to a class of problems. There is a sense of achievement in saying, “I have created a library that cleanly solves X problem in an optimal way.” But, it’s even more satisfying if that library becomes widely used. A hallmark of a great engineer is often the tools they created that others adopt. This professional pride drives developers to generalise solutions beyond one-off fixes. Rather than just patching a bug in one project, a proud developer might spin it out into a framework or contribute a fix upstream so that the entire ecosystem improves. Hubris in its positive form leads to those feats of engineering that truly simplify life for everyone thereafter.

Business value

It’s not all high-minded idealism; there are pragmatic reasons too. In a business setting, reusability and abstraction save money and time. If a company can grab an off-the-shelf solution instead of funding a six-month engineering project, they will. Developers, being aware of this, often advocate for using proven libraries or services to meet deadlines. This has driven the rise of third-party APIs and cloud services that handle common functionalities: emailing, payments, maps, authentication, etc.. Startups today can launch a sophisticated product by composing trivialised services provided by other. They focus only on their core idea. Thus, the market rewards those who make complexity go away (the entire SaaS industry of “X as a Service” is basically about trivialising complex capabilities and selling them).

Developers employed in such environments internalize that reinventing the wheel is a waste of resources. This reinforces the culture of looking outward for pre-made solutions and contributes to the cycle of sharing: many companies open-source their tools because they know the community will improve them, to everyone’s benefit. In short, using and contributing to trivialised solutions is often the economically smart choice.

Maintenance and reliability

Another motivation is that a widely used solution is likely more reliable than dozens of obscure ones.

Edsger DijkstraSimplicity is prerequisite for reliability.

A codebase becomes simpler (from an outsider’s perspective) if it uses standard, well maintained components for common tasks. By using a popular library, you avoid the risk of writing your own subtle bugs. You trust the tried-and-true solution and thereby increase reliability. Every new line of code is a liability as well as an asset. This knowledge encourages us to prefer making something a non-issue (via an external solution) over dealing with all its complexity ourselves. When we automate deployment, we reduce the chance of human error. When we use an ORM instead of raw SQL, we reduce the chances of mistakes. A drive for quality and reliability pushes developers to use proven solutions.

In essence, developers self-trivialise because it aligns with both our personal virtues (laziness, impatience, hubris) and our community values (sharing, collaboration), not to mention practical business sense.

Are we solving ourselves out of a job?

If we keep trivialising every aspect of development, what’s actually left for software developers to do? Are we, in effect, solving ourselves out of our own jobs by making things so simple that anyone can do them (or so that machines can do them)? The current age of AI and no-code tools make this debate more relevant than ever.

Moving up

History shows that as lower level tasks become trivial, developers don’t become irrelevant. Instead they move to higher level problems. When assembly language abstracted machine code, programmers could focus on algorithms and data structures in higher level languages. When open source took care of web servers and database engines, developers could focus on application logic and new features. Now, if AI and no-code handle the routine coding, developers will likely focus on architecture, problem framing, integration, and tackling new problems that aren’t solved yet.

The nature of the job changes, not its existence.

Even when a problem seems “solved for good,” the real world keeps turning: requirements change, new use cases appear, or technology shifts. The goal of automating yourself out of a job is never really achieved, because your role simply shifts to the next level of challenges. Wether you like this next level of challenges, however, is a different question.

Never ending demand for new solutions

The software industry often finds new problems as fast as it resolves old ones. Each layer of abstraction enables building more ambitious solutions, which in turn present new problems. As long as humans have new ideas and needs, there will be complex problems that aren’t solved yet. Developers will be needed to understand those problems, and perhaps eventually trivialise them in turn. The frontier keeps moving, and developers move with it.

Changing skill sets & AI

The average developer of tomorrow may not need the same skills as one from yesterday. Certain low level skills might disappear from daily work (just as manual memory management or assembly coding, mostly). Instead, skills in integrating systems and understanding larger architectures, as well as deciding between using off-the-shelf solutions vs customising becomes important. Also, “soft” skills like domain knowledge and creative thinking may become more relevant. If AI can write the boilerplate, a developer’s value might lie more in deciding what to build, making sure it’s correct, and guiding the AI. We may become more like curators for our tools: verifying outputs and setting constraints.

Coding by hand could become a more specialised activity in niches where custom work is still necessary or where the abstractions don’t yet exist.

More maintenance

Nothing stays trivial on its own.

Open-source libraries need maintainers; abstractions need to be refined while underlying platforms change. There will always be work in maintaining and improving the “solved” solutions themselves. For example, there are engineers whose full-time job is improving the Linux kernel, or the Python language, or an AI model’s code generation. These jobs are about managing complexity at the core so that the masses of developers don’t have to. As long as we test the limits of what is possible, someone has to take care of the solutions that trivialise things. And as systems become more mature, there is complexity in their scaling and reliability; areas that require plenty of engineering.

Risks, downsides and fundamentals

One risk of extensive trivialisation is that developers can become detached from the fundamentals. I personally feel like this particular risk is more prevalent right now, than ever before during my career. Especially because of gen AI. If someone relies on abstractions without understanding them at all, there’s danger when things inevitably go wrong. Even the best high level solutino can expose complexity when it breaks. The left-pad incident is a funny example. It shows that perhaps developers had trivialised a bit too much.

Another concern is relying too much on third party solutions. If every part of your stack is trivial thanks to someone else’s hard work, that’s a dependency risk.

In the long term, developers will need to balance the convenience of trivialisation with the wisdom of knowing how things work “under the hood”, at least at a conceptual level.

The endgame

Could there be a point where everything in software is trivial, and developers have effectively engineered themselves out of existence? That seems unlikely. As long as software is being written to solve human problems, and those needs evolve, we will keep finding new “unsolved” problems. It might not look like the coding job of today; it might be more about working alongside AI, or focusing on human-computer interaction design, or something we can’t even foresee, but the essence of creating solutions from ideas will remain.

My personal hope is that, the more we trivialise the mechanics of software creation, the more we free up creativity. We might see an era where the bottleneck is no longer how to implement something, but what to implement. In that scenario, developers (or whatever we call the role) become closer to product visionaries and domain experts who use tech as a medium. Trivial software construction could let future developers focus on solving broader societal or scientific challenges via software, rather than wrestling with boilerplate.

To sum up, the self-trivialisation of software development is not so much a path to obsolescence as a driver of evolution. It has always been present: we solved and abstracted away the need to manually manage memory, to code UIs pixel by pixel, to manage servers manually, and so on. Our focus shifts upward and outward, but the heart of the job; using technology to solve problems, remains!

In embracing self-trivialisation, we are continuously redefining our role. Today’s trivialities were yesterday’s breakthroughs. Today’s challenges, once solved, will be the trivialities of tomorrow. Our profession is, in a way, a planned obsolescence. We strive to obsolete our own past work by making it invisible and easy. And in doing so, we accelerate the field forward.

Conclusion

The self-trivialisation of software development is about a core ethos of our industry: solve hard problems; not just for yourself, but in such a way that no one else ever has to solve them from scratch again. From the earliest abstractions in programming to today’s AI-assisted coding, the common thread has been to turn complex problems into routine operations.

As developers, we find ourselves in a continuous balancing act between complexity and simplicity. We embrace complexity long enough to master it, and then we encapsulate it, hide it behind an interface, or automate it away, making it simple (or at least simpler) for the next person. In doing so, we do trivialise aspects of our own work, but this allows us (and the next generation of developers) to reach higher. It is intellectual altruism combined with efficiency (or laziness?).

Looking forward, self-trivialisation projects a future where developers are even more empowered by tools and abstractions. It also projects a future where we have to keep learning and adapting, because what was a relevant skill yesterday might be handled by an AI or a platform tomorrow. Our value lies in how quickly we can leverage new trivialities to create something innovative, and how effectively we can identify the next big unsolved problem to sink our teeth into.

In the end, rather than making developers insignificant, this cycle has a habit of making developers even more crucial; but operating at a different level. The world will always have problems in need of creative solvers. And as long as that’s true, those solvers (us developers) will keep doing what we’ve always done: making the hard things easy. The tools and methods will change, but the mission remains: take the complex and make it feel trivial.